UNHAPPY DEATHDAY, SERGIO!

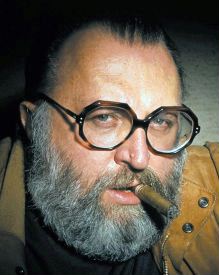

Sergio Leone, my favorite director, died 26 years ago today. As a tribute to Leone’s life and career I’ve assembled a few clips of his films accompanied by some choice quotes from the man himself. Unhappy Deathday, Sergio! Viva Leone!

A Fistful of Dollars:

“When they tell me that I am the father of the Italian Western, I have to say, ‘How many sons of bitches do you think I spawned?’ There was a terrifying gold rush after the commercial success of A Fistful of Dollars. It wasn’t as if the Italian Western had been taken up by many serious producers or serious directors; it was simply a terrifying gold rush, and most of them built castles in the sand instead of on rock – the foundations just weren’t there.”

“I feel that A Fistful of Dollars made a certain breakthrough in terms of the presentation of violence. Sam Peckinpah told me that The Wild Bunch could not have been made if it hadn’t been for my films. He said that A Fistful of Dollars launched ‘a new kind of cinema.’”

“I wanted Lavagnini, who had composed the music for The Colossus of Rhodes, to write the score. The producers had spoken to me of Ennio Morricone and showed me Showdown in Texas which seemed horrible to me; the music sounded like a poor man’s Tiomkin. The producer insisted on my meeting Morricone. I went to his house and he had me listen to a piece that the producers had rejected and which I was later to use in the finale of the film. Afterwards we listened to a record of something he’d written for an American baritone which immediately impressed me. I asked him to keep the basic elements. We had the principal motif, only the singer was lacking. I proposed having someone whistle it and thus the firm of Alessandroni and Company was born.”

“The duel in Fistful reverses all sorts of conventions. It’s a theatricalized duel in the arena where the moment of truth takes place. Not face to face! There’s the phrase, ‘When a man with a .45 meets a man with a rifle, the man with a pistol will be a dead man.’ And I amused myself by proving the contrary. When Volonte’s rife is empty, Eastwood places his pistol on the ground. The duel begins. We follow his technique of picking up his firearm and loading it. We also follow his opponent’s technique. The rifle takes longer. So: Volonte loses.”

“The day after A Fistful of Dollars opened in Rome, one of the reviews really got to me – because it was written by an enemy of mine. It was a thoughtful review which even suggested connections between Fistful and the films of John Ford. So I picked up the telephone and said to him, ‘I’m touched, truly touched by your support. Thanks you so much. I’m so glad you were able to bury our disagreements.’ And this was his reply: ‘But what on earth have you got to do with A Fistful of Dollars?’ He was the only critic in town not to have found out that behind the name of ‘Bob Robertson’ on the credits was Sergio Leone. Since then, with monotonous regularity, has always panned my films.”

“The story is told that when Michelangelo was asked what he had seen in one particular block of marble, which he chose among hundreds of others, he replied that he saw Moses. I would offer the same answer to the question why did I choose Clint Eastwood, only backwards: What I saw, simply, was a block of marble. And that was what I wanted.”

For a Few Dollars More:

“When Eastwood was offered the second film, For a Few Dollars More, he said to me, ‘I’ll read the script, come over and do the film, but please, I beg of you, one thing only – don’t put that cigar back in my mouth!’ And I said, ‘Clint, we can’t possibly leave the cigar behind. It’s playing the lead!’”

“I flew to L.A. to find Lee Van Cleef. I saw him walking in the distance and he looked just exactly right. He looked like a grizzled old eagle. I turned to my production manager and said, ‘Just sign him up here and now. I don’t even want to speak to him, because if I do it might make me decide not to take him, and if I did that I would be making a big mistake. He is so perfect for the film that I don’t want to hear a word of what he has to say.’”

“The character of the bounty hunter, the bounty killer, is an ambiguous one. They called him “the gravedigger” in the West. He fascinated me because he demonstrate a way of living in this land, and at that time. You must kill to survive.”

“In the final duel, Clint obliges the colonel to prove his professionalism, once and for all, at the moment of truth. He gives him his chance, but the colonel must move fast because Indio is fast on the draw! And Clint will not help him in this closed situation. He’ll remain a spectator. If the colonel is beaten, then he will avenge him. But the essential thing is to preserve his colleague’s moment of truth. This is much less banal than a saloon duel.”

“The lives of two bounty hunters depend on a perfect knowledge of the tools of their trade: guns. I couldn’t invent imaginary objects. I needed to be exact from the technical point of view, so I found exact descriptions of all the types of weapons of that period and ordered them to be remade for the film. But authenticity wasn’t enough. I had to be precise about ballistics and range as well. To nourish my fairy-story with a documentary reality.”

“I did not ask Morricone to read the script. I told him the story as if it was a fairy-tale. Then I explained the themes I wanted. Each character had to have his own theme. But I spoke Roman-fashion, with plenty of adjectives and comparisons, making sure everything was clear. Then he worked at the composition and brought me some very short themes, one for each character. He played them to me on the piano. This would continue until he’d composed a piece which inspired me – because it was me the music had to inspire, not Ennio! When a passage pleased me, I’d say, ‘That’s the one!’”

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly:

“I had always thought that the ‘good’, the ‘bad’ and the ‘ugly’ did not exist in any absolute, essential sense and it seemed to me interesting to demystify these adjectives in the setting of a Western.”

“What interested me was the absurdity of war. I wanted to show human imbecility in a picaresque film. The key line of the film is the comment made by a character about the battle on the bridge: ‘I have never seen so many imbeciles die so pointlessly.’”

“I wanted Eli Wallach because of a gesture he makes in How the West Was Won when he gets off the train and talks to George Peppard. He sees a child, Peppard’s son, and suddenly turns and shoots him with a finger. That made me realize he was a comic actor of the Chaplin school.”

“Charlie Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux, one of the finest films I know, had a strong influence on The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Chaplin’s film looked at the chaotic and absurd aspects of an era in which a hero who has murdered several women could say, at his trial, ‘I am just an amateur at homicide compared with Mr. Roosevelt and Mr. Stalin, who do such things on a grand scale.’ Verdoux is the model of all the bandits, all the bounty hunters. Put him in a hat and boots, and you have a Westerner.”

“In The Good, the Bad and the Ugly each character had his musical theme. I was representing the route-map of three beings who were an amalgam of all human faults and I needed crescendos and spectacular attention-grabbers which nevertheless chimed with the general spirit of the story. So the music took on a central importance. It had to be complex, with humor and lyricism, tragedy and baroque.”

“My Westerns have been compared with melodramas. If this comparison arises from the importance of music in my films, then I feel flattered. I have always limited the use of dialogue, so that spectators can use their own imaginations while they observe the slow and ritual gestures of the heroes of the West. If it is true that I have created a new-style Western, with picaresque people placed in epic situations, then it is the music of Ennio which has made them talk.”

“The final duel was a sequence which gave me the greatest satisfaction, especially from the editing point of view. The picaresque journeys all come to a conclusion within it. I always enclose the final sequence, the denouement of my films, within the confines of a circle. It is the arena of life, the moment of truth at the moment of death. This wasn’t a whim on my part. The idea of the arena was crucial. With a morbid wink of the eye, since it was the dead who were witnesses to this spectacle. I even insisted that the music signify the laughter of corpses inside their graves. The first three close-ups of each of the actors took us an entire day. I wanted the spectator to have the impression of watching a ballet. And I had to accumulate shots of their cunning in action: their looks, their gestures, their hesitations. The music gave a certain lyricism to all these ‘realist’ images – so the scene became a question of choreography as much as suspense.”

Once Upon a Time in the West:

“I wanted to do a film which was a dance of death, or a ballet of the dead. I wanted to take all the most stereotypical characters from the America Western – on loan! The finest whore from New Orleans; the romantic bandit; the killer who is half-businessman, half-killer, and who wants to get on in the new world of business; the businessman who fancies himself as a gunfighter; the lone avenger. With these five most stereotypical characters from the American Western I wanted to present an homage to the Western at the same time as showing the mutations which American society was undergoing at the time. So the story was about a birth and a death. Before they even come on to the scene these stereotypical characters know themselves to be dying in every sense, physically and morally – victims of the new era which was advancing.”

“We wanted the feeling throughout of a kaleidoscopic view of all American Westerns put together. But you must be careful of making it sound like citations for citations’ sake. It wasn’t done in that spirit at all. The references aren’t calculated in a programmed kind of way; they are there to give the feeling of all that background of the American Western to help tell this particular fairy tale. They are part of my attempt to take historical reality – the new, unpitying era of the economic boom – and blend it together with the fable.”

“The rhythm of the film was intended to create the sensation of the last gasps that a person takes just before dying. Once Upon a Time in the West was, from start to finish, a dance of death. I wanted to make the audience feel, in three hours, how these people lived and died…”

Once Upon a Time in the West Opening: The Sound as a Storyteller from Pablo Valverde on Vimeo.

Duck You Sucker:

“Mexico became a pretext to evoke wars and revolutions. In certain sequences, I signal events from other places and times: the flight of the king; the Ardeatine Caves massacre; the ditches and death pits of Dachau and Matthausen. I even chose a face resembling the young Mussolini and dressed him up in a uniform. These are signs which are there to connote all wars and revolutions.”

“But at the heart of the film, and my essential motivation, was the theme of friendship which is so dear to me. You have two men: one naïve and one intellectual. From there, the film becomes the story of Pygmalion reversed. The simple one teaches the intellectual a lesson. Nature gains the upper hand and finally the intellectual throws away his book of Bakunin’s writings. You suspect damn well that this gesture is a symbolic reference to everything my generation has been told in the way of promises.”

“Me, I live apart and don’t give a damn about anything. At the end of the war, like many Italians, I had illusions and dreams. I believed in revolution – in the mind if not in the streets. I dreamed about a more just and humane society, where wealth was more evenly distributed. After all, my father struggled against Fascism and I came from a socialist family. Let us just say that I am a disillusioned socialist. To the point of becoming an anarchist. But because I have a conscience, I’m a moderate anarchist who doesn’t go around throwing bombs. I mean, I’ve experienced just about all the untruths there are in life. So what remains in the end? The family. Which is my final archetype, handed down to us from prehistory. What else is there? Friendship. And that is all. I’m a pessimist by nature. With John Ford, people look out the window with hope. Me, I show people who are scared even to open the door. And if they do, they tend to get a bullet right between the eyes.”

“I suffered a lot on that film. The shooting, the plots, the problems. And the editing which took such a long, long time. I’m attached to the film as one might be to a disabled child.”

ONCE UPON A TIME: THE REVOLUTION: Opening Sequence by bongolicious

A Fistful of Dynamite

— MOVIECLIPS.com

Once Upon a Time in America:

“Once Upon a Time in America is my best film, bar none. I’m glad I made it, even though during filming I was as tense as Dick Tracy’s jaw. It always goes like that. Shooting a film is awful, but to have made a movie is delicious.”

“I’m trying to do a film that can’t easily be categorized. It’s not a realistic film, not historical. It’s fantastic, it’s a fable. I force myself to make fables for adults.”

“Time and the years are one other essential element in the film. The characters have changed, some of them rejecting their past identities and even their names – and yet in spite of themselves, they have remained bound to the past and to the people they knew and were. They have gone separate ways; some have realized their dreams, for better or worse; others have failed. But growing from the same embryo, as it were, after the careless self-confidence of youth, they are united again by the force that had made them enemies and driven them apart – Time.”

“And it is this unrealistic vein that interests me the most, the vein of the fable, though a fable for our own times and told in our own terms. And, above, all, the aspects of hallucination, or a dream-journey, induced by the opium with which the film begins and ends, like a haven or a refuge.”

“The scene of the charlotte russe in the stairwell is an homage to Charles Chaplin. It is not an imitation of him or plagiarized from a sequence of his. It is simple evidence of my love for him. And I think he would have filmed the situation in this way.”

“I want to say how much the truncated version took the soul out of my work. A version of one hundred and thirty-five minutes was done for television. Everything was flatly chronological: childhood, youth and old age. Time is no longer a theme. There is no more mystery, journey, and opium smoking. It is an aberration. I cannot accept that the originalversion is too long. It has the exact duration it should have. After the screening at the Cannes Film Festival, Dino De Laurentiis told me it was wonderful but it was necessary to cut a good half hour. I told him he was in no position to tell me that. Because he makes films of two hours which seem to last four hours, while I make films of four hours which seem to last two. Dino cannot understand this. I added that this was the reason we never worked together.”

“I am aware that this film is different from my previous works. This time I worked in total clarity as to the correctness of what I was doing. No question. Not the slightest concern. I have no doubt. I was transported on a journey during which I was certain of a good result. I’m speaking of the making of the movie. I’m really happy to have waited fifteen years to do it. All this time was important. I reflected on this when I saw the finished film. And I realized that if I had done the film earlier, it would have just been one more movie. Now, Once Upon A Time In America, it is the film by Sergio Leone. And it’s me, this film. We can only succeed with such a film with maturity, white hair and a lot of wrinkles around the eyes.”

“It seemed to me important, at that precise moment in my life, to film the almost futile existence of a person who left no trace and whose sole strength was the sentiment of friendship. Something which has always touched me, and which I have treated in all my films.”

“Clint is a mask of wax. In reality, if you think about it, they don’t even belong in the same profession. De Niro throws himself into this or that role, putting on a personality the way someone else might put on his coat, naturally and with elegance; while Eastwood throws himself into a suit of armor and lowers the visor with a rusty clang. It is precisely that lowered visor which composes his character. And that creaky clang it makes as it snaps down, dry as a Martini in Harry’s Bar in Venice, is also his character. Look at him carefully. Eastwood moves like a sleepwalker between explosions and hails of bullets, and he is always the same – a block of marble. He had only two expressions: with or without a hat. Bobby, first of all, is an actor. Clint, first of all, is a star. Bobby suffers. Clint yawns.”

Once Upon a Time in America (scene) by dm_50218e8e7e221

Posted on April 30th, 2018 by Mat Viola

Filed under: Miscellaneous