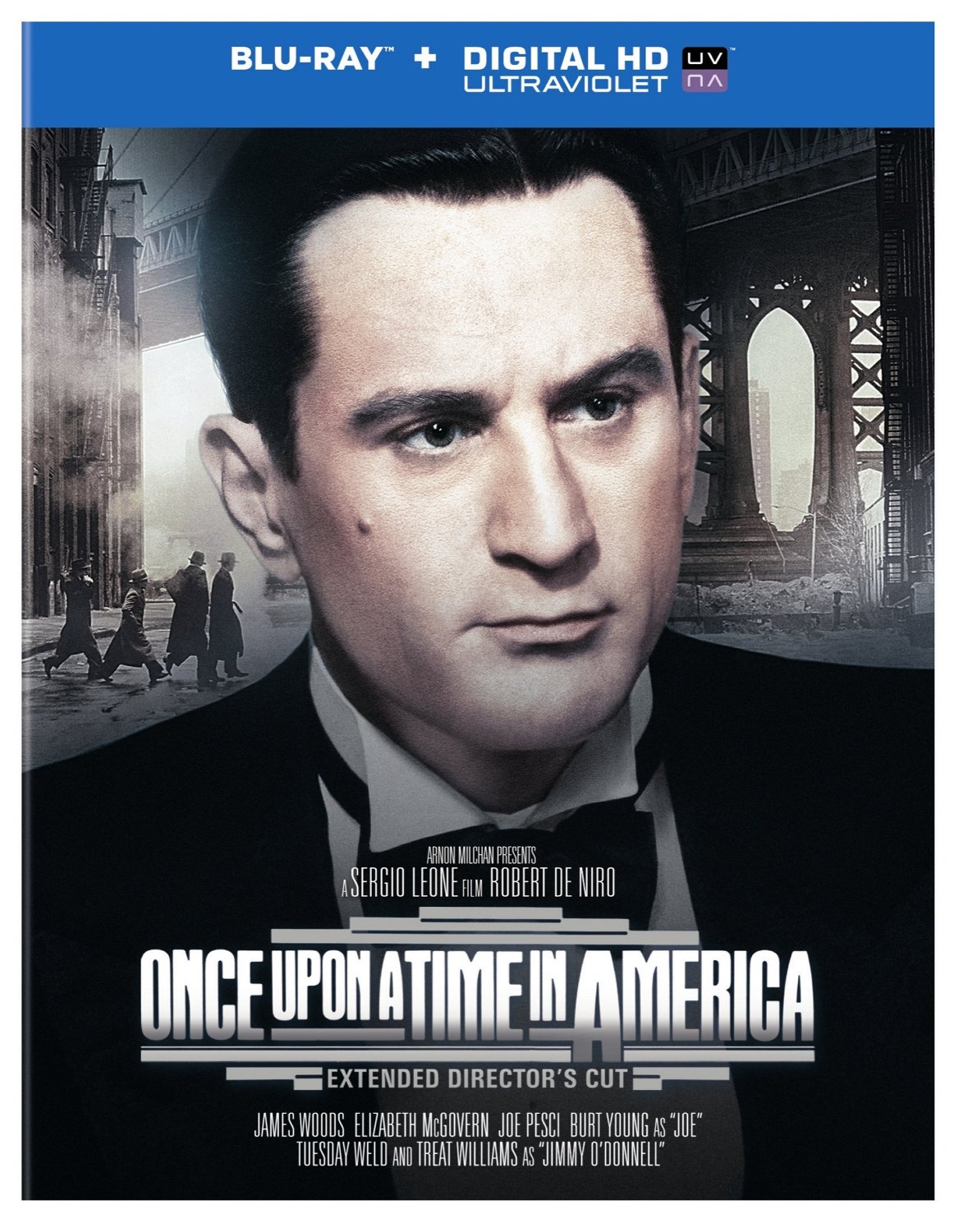

After the restored longer version of Once Upon a Time in America was shown at the 2012 Cannes Film Festival (which I wrote about here), the film was promptly removed from circulation “pending further restoration work.” Not much has been written about it since, but now, on September 30, Warner Bros. is finally releasing the extended – and, presumably, “further” restored – version on Blu-ray. Although press reports and reviews will doubtless tell you that this version more closely approximates Leone’s intended director’s cut, the reality is far more complex. First, there’s a small matter that nobody ever mentions: Leone preferred the 229-minute version. How do I know this? Because he said so: “the version that I prefer is this one.”

Here’s the full quote:

“Then there is the very long one that has never been edited and which lasts fifty minutes longer. Four and a half hours. But we rejected the idea of two parts on TV. It is so intricate that it has to be done in one evening. And besides, let’s be honest: this one is my version. The other perhaps explained things more clearly and it could have been done on TV in two or three parts. But the version that I prefer is this one, that bit of reclusiveness is just what I like about it.”

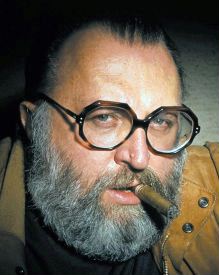

[Source: Sergio Leone: The Great Italian Dream of Legendary America by Oreste De Fornari]

This raises obvious questions: If Leone were alive today would he even want to have these scenes reinstated? Would he want a bunch of technicians, splicers and knob-twiddlers, many of whom had no previous association with the film, tampering with his *preferred* version without his consent? We will never know, of course, the extent to which Leone would have approved of this longer version. And that’s the point. We can’t know. So, please, let’s not refer to it as the “Extended Director’s Cut,” as is stated so misleadingly on the cover of the Blu-ray.

A different albeit related question is this: did Leone actually assemble a fully edited, ready-for-distribution 270-minute director’s cut in 1984? Most fans assume so, but considering the ample evidence to the contrary, I have my doubts. Let’s review the evidence:

1) In his 1988 interview with De Fornari, Leone is quoted as saying:

“Then there is the very long one that has never been edited…”

The quote contradicts the notion that Leone finished editing the longer version. It is, of course, possible that he was mistranslated. After all, in an earlier interview he’s quoted as saying the exact opposite: that the scenes had been edited. Perhaps in the later interview Leone used the word “edito” which sounds like “edited” but which Google translates as “published” and which could, I suppose, be interpreted as “released.” So he might have said that the missing scenes had never been released.

But…

2) In the Cannes press kit, Davide Pozzi, Director of L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory which performed the restoration, wrote:

“Technically, the homogeneity of the unedited scenes was the biggest problem, as unfortunately the negatives for these scenes no longer exist.”

Was Pozzi mistranslated too? I doubt it since I think he’s fluent in English. So what does he mean by “unedited scenes” if not that the scenes were…unedited?

I don’t know, maybe we can construe “unedited scenes” to mean “scenes that need to be reinserted from where they were removed.” And why not? Doesn’t Gian Luca Farinelli say, in that very same press kit, that “beginning and end frames of the cut scenes allowed us to identify the exact place they were deleted from.”?

So there you have it. All they had to do was take a beginning frame from here, an end frame from there, and reinsert them whence they came. Finito!

But…

3) In an Italian article from 2011, Andrea Leone, Sergio’s son, said “Il montaggio degli inediti e una ricucitura complessa,” which roughly translates as “the editing of the unreleased footage needs complex re-stitching.” (Note: in the context of filmmaking, “montaggio” refers to editing.)

Here we have a sentence containing three words that seem to refer to or could be interpreted as “editing” – montaggio, ricucutura and inediti. (Note: the Italian translation of “unedited” is, according to Google, “inediti.”) Whatever the precise translation, one thing is certain: the process to reinsert the missing scenes would be “complessa” – i.e., complex.

Hmm, if all they had to do to arrive at Leone’s fabled director’s cut was insert the unreleased (and supposedly fully edited) footage back into the existing 229-minute version, why would Andrea say that it would be a complex editing process?

Come to think of it, editors routinely leave extra footage at the head and tail of frames on rough cuts so that the shots can later be trimmed for content, rhythm, and running time. It is common practice, is it not, for editors to significantly whittle down the running time of rough cuts by the time the film is released? So, yeah, we know where the missing scenes were cut from (the script pretty much tells us that anyway), but so what? That doesn’t mean they were taken from a completely edited workprint – i.e., the fine cut.

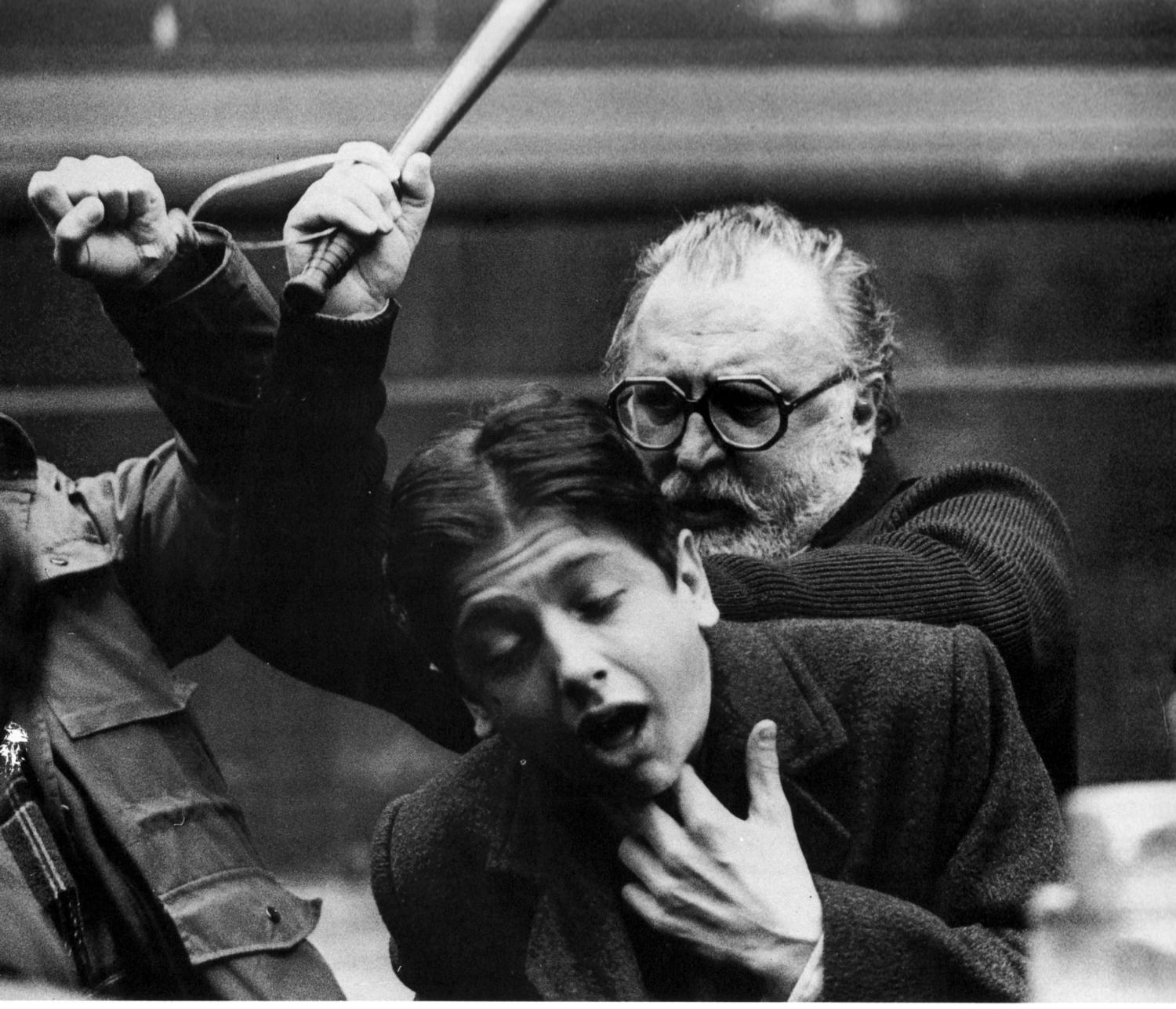

In his 1984 interview with Cahiers du Cinema Leone discusses the film’s duration, saying that he was given carte blanche to make a four-and-a-half hour version, but then…

“Four months after the start of editing, they said to me no, it is not possible. They demanded that I cut the film. I did not want to go back to the first concept which was three hours. I cut as much as I could…”

This is, I think, telling: Leone knew that a four-and-a-half hour version was out of the question two months *before* he finished editing the film. It’s not as if they demanded he shorten the film *after* he’d assembled a fully edited 270-minute fine cut. I suspect, then, that Leone excised around 40-50 minutes of footage from an *incomplete* workprint, not from the *fine* cut, with the idea of later assembling a longer version for Italian TV, but never got around to fine-tuning the scenes.

According to Leone’s biographer, Christopher Frayling:

“Leone had ten hours of usable footage in the can. With help from editor Nino Baragli, this was pruned to six hours. Then, finally accepting that there was unlikely to be a two-part version, Leone delivered a *fine cut* of three hours and forty-nine minutes.”

So it sounds like the “fine cut” – the one that results from trimming down the rough cut – was three hours and forty-nine minutes, not four hours and twenty-nine minutes. If so, that means the missing scenes never made it all the way through the most crucial creative phase of the editing. How do we know the extent to which the scenes had been edited? Were they completely edited, up to and through post-production, or were they only partly edited and/or in need of additional post-production work?

Of course, it was Andrea Leone, after all, who said reinserting the missing scenes would be a “complex” task, and we all know from the fiasco of the premature release of the restored version that Andrea has his head lodge in his asshole up to his Adam’s apple, so it stands to reason that he was just talking shit.

But…

4) Reportedly, Morricone and Fausto Ancillai, the film’s original sound editor, helped supervise the restoration, which suggests, at the very least, that the sound and music in the missing scenes hadn’t received proper post-production attention.

Admittedly, I don’t know the exact contributions Ancillai and Morricone made to the restoration. All I know is what little has been reported of their involvement. I think Variety was the first to report Ancillai’s role as supervisor, and Pozzi thanks him in the aforementioned press kit for his support during the restoration process.

Interestingly, Pozzi did not thank Morricone, which might indicate that the composer’s involvement was minimal, I don’t know. Farinelli mentions Morricone in relation to the restoration in this 2011 article but it’s in Italian and the Google translation is ambiguous:

“It will be a challenging process and we are at the beginning. A job that will require at least a year, also because in addition to the frames, there are the sound effects and the soundtrack of Morricone, who is added to the work of replacement.”

I can’t tell if Farinelli is saying that Morricone will work on the new scenes or simply that the sound and music need additional work/enhancement. Maybe someone who understands Italian can interpret this.

This French translation of the Italian article is less ambiguous, and if it’s closer to the mark, then there’s good reason to believe that Ancillai and Morricone contributed additional sound and music to the excised scenes.

“It’s a real challenge ahead of us today. A job that will require almost a year, because in addition to the image, there is the sound and music of Ennio Morricone to be added.”

Leone makes another telling statement in the Cahiers interview:

Cahiers: How was the sound done in the movie?

Leone: Everything was in direct sound, with Jean-Pierre Ruh, who won an Oscar for Tess. But it was necessary to *post-synchronize* some scenes because sometimes I try shooting with the film music and the actors who have rehearsed with it sometimes prefer to film with it and to *dub afterwards* since it gives them a certain atmosphere.

So just because Leone shot the missing scenes with direct sound does not mean he completed post-production work on the dialogue, let alone the effects and music.

Most directors do not play music on the set, so Leone was unique in this regard, but even under normal circumstances dialogue is often modified and/or replaced during post-production. Moreover, whether scenes are shot silent or with direct sound, the music and sound effects get mixed in afterwards, during the post-synchronization process.

Given Leone’s operatic style and imaginative sound designs, the mixture of sound and music was a particularly important element of his cinema. To put the matter into stark relief, imagine if the opening of Once Upon a Time in the West, with its marvelous symphony of sound effects, or, more to the point of this post, the sequence in Once Upon a Time in America with the ringing phone echoing persistently through Noodles’ guilt-ridden flashback, had been excised before going through Leone’s creative sound mixing process! That phone rings 24 times at gradually increasing intervals over a span of 3 minutes and 43 seconds. How would the scene play if left to the devices of Andrea and his knob-twiddlers? How many times would the phone ring? Would the sequence climax with that piercing electronic shriek? I’d say “fat chance” but that would be an insult to fat chances. No wonder they enlisted the film’s original sound editor to supervise the restoration!

To be fair, the majority of the missing scenes appear to be heavy on expository dialogue, so perhaps the situation isn’t as serious as it might have been.

But Leone’s forte lay in his operatic style, his flair for creating dramatic marriages of image, sound and music, which likely inclined him to excise these talky scenes. And if, as I suspect, Leone cut the scenes before post-production and put them aside for safekeeping with the intention of fine-tuning them later, but ultimately abandoned plans to assemble a longer version, then, well, I’m afraid the Leone clan’s decision to reinsert the scenes was a doomed venture from the beginning.

When Raffaella first announced the discovery of these scenes in 2006, she said:

“We want to restore 40 minutes of deleted scenes we have found. Mind you, though: we will not reassemble the movie, which will stay what my father did.”

Yet she couldn’t leave well enough alone. Instead, she did precisely the opposite of what she said she would do: she *changed* what her father did. One has to wonder why. Did Leone’s secret diary reveal that he preferred the extended cut after all? Did Leone’s ghost encourage her to go forth with the project? Or, perhaps, were there more, shall we say, financial considerations afoot? Did she, her brother, and their moneymen calculate that it would be more profitable to reinsert the scenes? Maybe plastering “Extended Director’s Cut” across the Blu-ray cover would fill their coffers. But would the siblings Leone really sell out papa Leone for a stinking fistful of denaro? Well…maybe.

In any case…

This comment by Pozzi makes a mockery of the notion that the newly restored longer version is Leone’s director’s cut:

“Technically, the homogeneity of the unedited scenes was the biggest problem, as unfortunately the negatives for these scenes no longer exist. The only materials available were discarded strips of working positives which had been badly preserved. Making this task even more difficult was the fact that the working positives had been printed without particular care, as originally they were part of the working copies which circulated between the assistant editors and sound editors as a work reference.”

Perhaps someone more familiar than I with the ins and outs of the editing process can straighten me out here, but if the missing scenes were unedited, if the negatives no longer exist, if the only materials available were discarded strips of working positives that had been badly preserved and carelessly printed, and if assistant editors and sound editors had used these copies as a work reference, on what possible grounds can a case be made that the reinsertion of these scenes into the existing film somehow constitutes Leone’s director’s cut?

Moreover, that these scenes were used as a work reference suggests, does it not, that they were still in the process of being edited? So even if Leone had assembled a complete 270-minute director’s cut in 1984 (which remains questionable), who’s to say that these “discarded strips of working positives” had been edited in the same way and to the same extent as the corresponding footage that made it into the alleged 270-minute version?

The ultimate question – the long and the short of it, I suppose – is this: given the above facts, how do we know with anything approaching certainty whether the missing scenes had been fully edited, partially edited, or not edited at all? Which ones, if any, made it all the way to the fine cut? Maybe some did. Maybe others never made it past the rough cut. Maybe others needed post-production tweaking.

At least one scene was likely removed at the rough cut stage. Frayling says that Leone excised the chauffeur scene *during shooting* due to his reservations about producer Arnon Milchan’s acting ability, a well-founded concern given that the confrontational scene involves an amateur with no acting experience going up against the greatest actor of his generation. According to Leone’s trusted long-time assistant, Luca Morsella, whose close day-to-day contact with Leone surely gave him privileged insight into the director’s mentality and decision-making process, “Sergio had promised the part of the chauffeur to Milchan…but lost his nerve about this. He was worried that having taken so much trouble over casting everyone else, this might not work. So he said no. There was a row with Sergio, who finally agreed to shoot it. He shot it then cut it, and then told interviewers Milchan had made him cut it!”

Elizabeth McGovern, meanwhile, expressed grave doubts about her Cleopatra scene, not only because she felt she lacked the acting chops to pull off Shakespeare but also because “it stopped all the action…and was very strange to have a death scene Kabuki-style at that point in the movie.” She, for one, was happy to see it go. Frayling shares McGovern’s assessment of the scene and of herself, calling the scene “awful” and McGovern “no Shakespearean actress.” One has to wonder if Leone too harbored doubts; this might be the scene he least regretted cutting and the one he’d least want reinserted.

Still, in the end, it might turn out that the scenes did travel all the way through post-production and that Leone did assembled a complete, release-ready 270-minute director’s cut in 1984. Maybe such a cut really existed, despite good reason to think otherwise. I don’t know.

I *do* know that, however many minutes of shitty looking footage Andrea and Raffaella manage to splice into their father’s 229-minute version, the newly restored longer version is not now, nor will it ever be, a true Leone-approved director’s cut. This is so for the following reasons:

1) Leone preferred the 229-minute version:

“Let’s be honest: this one is my version. The other perhaps explained things more clearly and it could have been done on TV in two or three parts. But the version that I prefer is this one, that bit of reclusiveness is just what I like about it.”

To me, that’s the final word on the subject, straight from the lion’s mouth, so to speak.

2) Leone is dead. So unless his ghost directed the restoration from on high, I’m guessing he never gave Andrea, Raffaella, Scorsese, his personal chef, or anyone else approval to reinsert the scenes.

3) Leone ain’t no ghost. Which means he did not participate in the restoration of *his* film. And that means he had no input into how the editing of the missing scenes was handled. So how then can the restoration be the director’s cut if the director wasn’t around to make decisions about how best to cut it?

4) Just because Leone might not have wanted to remove the scenes in 1984 does not mean that he’d want to reinsert them today. Maybe he’d want to put back all the scenes. Or none of them. Maybe he’d want to reinsert the Louise Fletcher scene but leave out the new one with Treat Williams. Or vice versa. Maybe he’d decide to burn the chauffeur scene to spite Milchan. Maybe he’d choose to shorten a scene, or add a sound effect, or employ Morricone’s score in some idiosyncratic way. We’ll never know. Because he’s dead.

As far as I’m concerned, this newly restored version, or any other version Raffaella and Andrea decide to cobble together in the future, is nothing more than an approximation of a director’s cut Leone envisioned once upon a time.

That said, I can’t wait to see it! And I hope the accompanying 32-page booklet addresses some of the above issues.

Postscript (10/3/2014): I am now in possession of the misnamed “Extended Director’s Cut.” I haven’t watched the film yet, but in the process of downloading a digital copy, I happened to watch the pre-credits restoration notes. This caught my eye:

Additional sound restoration and sonorization of cut scenes: Fausto Ancillai and Ennio Morricone

Additional editing supervision: Alessandro Baragli and Patrizia Ceresani

“Sonorization” refers to the practice of adding music and effects to silent films. So there you have it: Fausto and Ennio contributed additional sound and music to the cut scenes. They “sonorized” the film!

That Alessandro Baragli, presumably Nino’s son, and Patrizia Ceresani provided “additional editing supervision” can mean only one thing: the cut scenes underwent editing of some kind. After all, there had to be editing going on in the first place for there to be a need for “additional editing supervision.” I guess Alessandro and Patrizia supervised the supervision of the editing. Perhaps Nino supervised the two career assistant editors from beyond the grave.

What a joke it is to claim that this is the “Extended Director’s Cut.” It should be called the “Deceased Director’s Additionally Edited and Sonorized Extended Cut.” But, of course, that wouldn’t fit on the cover of the Blu-ray.

Post-postscript (10/3/2014): Raffaella Leone makes some interesting remarks in this article:

Raffaella Leone: “This is the movie that our father showed us when he finished editing ‘his’ movie.”

Wait, what? “His” movie? Hmm, so then I guess Leone showed her the additionally edited and sonorized 251-minute version. And here I thought “his” movie was a completely edited, un-sonorized 270 minutes.

I wonder if Raffaella has ever read the 1988 interview her father did with Oresto De Fornari, in which he says:

Sergio Leone: “Let’s be honest: this one is my version. The other perhaps explained things more clearly and it could have been done on TV in two or three parts. But the version that I prefer is this one, that bit of reclusiveness is just what I like about it.”

Make no mistake, Raffaella: your father’s talking about the 229-minute version. Your father preferred the 229-minute version. Your father said it was *his* version, the one *he* prefers.

I have no idea what movie your father showed you, but whatever it was it wasn’t *his* movie, at least not the one he said was *his* in 1988. And it certainly wasn’t this additionally edited and sonorized 251-minute version just released on Blu-ray. Ya know, the “Extended Director’s Cut?”

Raffaella Leone: “To bring back to the screens that movie in its original version has been very difficult and time consuming.”

Wait, what? “bring back…that movie in its original version.”

“That movie.” What movie? The one he showed you once upon a time? *His* movie? So *his* movie was 251 minutes? I thought it was 270 minutes.

Questions for Raffaella (who no doubt reads this blog):

1) How can this movie be the “movie in its original version” if its original version was supposedly 270 minutes?

2) How can this movie be the “movie in its original version” if this movie in its present form was edited and sonorized?

3) Why did you decide to reassemble the movie, and change your father’s preferred 229-minute version, after you said “we will not reassemble the movie, which will stay what my father did”? Why didn’t you leave your father’s film alone, as you originally said you would?

4) What about the additional footage Scorsese supposedly has? Wasn’t that part of the original version? Or are you planning to release an even more original “original version” in the future with even more original footage from your father’s ever-evolving director’s cut?

Posted on September 28th, 2014 by Mat Viola

Filed under: Miscellaneous | Comments Off on ONCE UPON A TIME IN AMERICA – EXTENDED CUT (BLU-RAY)